Why banning 'harmful' online speech is a slippery slope

Such moves can easily lead to a disastrous shrinking of space for much-needed open discourse and dissent

The mob attack on Capitol Hill on January 6, instigated by President Trump in the hope of thwarting or at least delaying the certification of President-elect Joe Biden's election victory, was unquestionably one of the most shameful episodes in the political history of the United States. Ironically, the failed insurrection may well be the beginning of the end of Trumpism. But the fallout from these tragic events could also include a far less welcome development: a rush to regulate, quash, and banish a wide range of expression regarded as potentially dangerous.

The swift move to permanently ban Trump (and some of his more extreme supporters) from Twitter and other social media has prompted warnings about speech suppression even from people with little sympathy for the soon-to-be-ex-president, from the American Civil Liberties Union to German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Russian dissident Alexei Navalny. Then, Parler, a nearly unmoderated Twitter alternative favored by the right, went dead after Google and Apple dropped its app from their online stores and Amazon booted it from its web hosting service. This raised more concerns about the ability of a few mega-corporations to drastically curtail online access for undesirables. New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg, who believes that both Trump and Parler deserved to be de-platformed, writes that "it's dangerous to have a handful of callow young tech titans in charge of who has a megaphone and who does not."

Trump's ban, it should be noted, was brought on by his barely veiled instigation of unrest in an explosive situation; arguably, too, he repeatedly violated Twitter rules with impunity prior to last week. Likewise, Parler has been a cesspit of hateful, unhinged, and violent postings that violate Amazon's terms of service. While the United States has extremely strong legal protections for speech, they cover only government censorship, not restrictions by private corporations (though, as Goldberg and others have noted, the situation becomes alarming when a few corporations can effectively cut off a speaker from mass audiences). And at least some of the speech targeted in last week's crackdown was almost certainly illegal even under American law, since it poses a clear danger of inciting imminent violence.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But could the understandable backlash against extremism also fuel an already existing trend of speech- and thought-policing toward any views that run counter to progressive dogma?

Already, a number of writers on the left have tried to argue in mainstream venues that the assault on Capitol Hill shows the need to curb a wide range of "bad" discourse.

Vox culture critic Aja Romano blamed the Capitol Hill riot on far-right internet activity supposedly traceable to GamerGate, a 2014 videogame-community blow-up variously described as a harassment mob or a revolt against cronyism and "political correctness" in gaming journalism. It would be beside the point to revisit GamerGate, a complex and often misreported online saga (though it is worth noting that an FBI investigation linked no known GamerGate participants to criminal harassment and that plenty of its supporters were and have remained politically and socially liberal). But one of Romano's recommendations stands out: Social media platforms, she wrote, must "learn how to shut down disingenuous conversations over ethics and free speech." By what criteria social media platforms can determine which conversations on these topics are "disingenuous" remains unclear, and one may be forgiven for suspecting that they will be mainly political.

Meanwhile, British writer and journalist Laurie Penny responded to the attack with a tweet urging no tolerance for "fascism":

Whether fists are an effective way to deal with fascists is very much an open question; in Weimar Germany, for example, street brawls between Nazis and Communists helped pave the way for the Nazis' rise to power. But, no less important, there is the question of how one defines "fascism" and which viewpoints should be seen as deserving "a fist to the face." Could opposition to abortion qualify? (Some abortion-rights activists certainly seem to think that anti-abortion activism warrants violent retaliation.) This is not an idle question: Thus, New York Times editorial board member Lauren Kelley, who focuses on coverage of gender issues and reproductive rights, has tried to link the events of January 6 to anti-abortion advocacy, even asserting that "the anti-abortion movement has been the canary in the coal mine" for the current surge of right-wing radicalism.

The push to shut down "fascism" has also resulted in attempts — so far, unsuccessful — by several prominent left-wing journalists including New York Times writer Sarah Jeong to get right-wing journalist Andy Ngo banned from Twitter. Ngo's offense is his hostile coverage of Antifa, the far-left movement that claims to resist right-wing violent extremism but frequently initiates mayhem and violence against various targets. (Just a few days ago, Antifa activists in Portland, where Ngo is based, confronted and assaulted the city's progressive mayor, Ted Wheeler, after he promised a crackdown on the group following a New Year's Eve rampage.)

While Ngo (with whom I was on friendly terms for a period of time) started out as a solid reporter on culture-war issues, his recent work can certainly be criticized as biased and often sloppy, and he can be faulted for getting too close to extreme elements on "his" side. But the same charges can be directed at many journalists on the left. And there is certainly nothing about Ngo's Twitter presence to justify his banning.

Meanwhile, activists in Portland have been mobbing a bookstore for carrying Ngo's new anti-Antifa book, Unmasked, in its online catalogue.

In recent months, attempts to de-platform or punish "harmful" speech have targeted criticism of violence and looting related to anti-racism protests, as well as arguments that troubled teens are being too readily steered toward medical gender transition. In such a climate, calls to de-platform "dangerous" expression can easily lead to a disastrous shrinking of space for much-needed open discourse and dissent.

Some argue that such concerns are misplaced and frivolous when far-right terrorism remains a clear and present danger. Adam Serwer, a writer for The Atlantic, summed up this view in a sarcastic tweet:

One could easily imagine a similarly snide response to concerns about civil liberties after September 11 ("Yes, nearly 3,000 Americans were murdered by terrorists. Yes, they came close to destroying the Capitol. But here's why the hysterical 'patriotic' reaction to this is far more dangerous"). Yet few people today would deny that our reaction to September 11 often put our liberties in jeopardy and chilled dissent. In the wake of January 6, perhaps we should heed that lesson.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Cathy Young is a columnist for Newsday and a contributing editor at Reason magazine. Her book Ceasefire!: Why Women and Men Must Join Forces to Achieve True Equality was published in 1999.

-

Book reviews: ‘Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism, and the Making of Modern America’ and ‘How to End a Story: Collected Diaries, 1978–1998’

Book reviews: ‘Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism, and the Making of Modern America’ and ‘How to End a Story: Collected Diaries, 1978–1998’Feature A political ‘witch hunt’ and Helen Garner’s journal entries

By The Week US Published

-

The backlash against ChatGPT's Studio Ghibli filter

The backlash against ChatGPT's Studio Ghibli filterThe Explainer The studio's charming style has become part of a nebulous social media trend

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

Why are student loan borrowers falling behind on payments?

Why are student loan borrowers falling behind on payments?Today's Big Question Delinquencies surge as the Trump administration upends the program

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

By The Week Staff Published

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

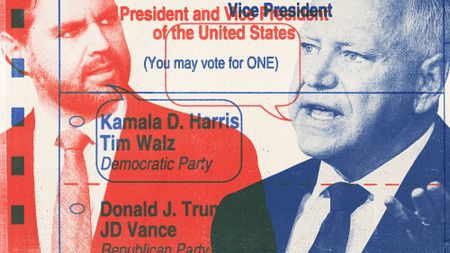

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK Published

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published